From an interior design perspective, ocean liners were venues for glamour, drama and escapism. As the catalogue for Ocean Liners explains, these ships were seen as “liminal spaces free from the conventions of terra firma”, where passengers would show off the latest fashion, hobnob with celebrities by the poolside and frequent restaurants, bars and lounges. As a backdrop to this fantasy world, artists such as Jean Dunand and David Hockey were commissioned to create artwork for the interiors (the former, golden lacquer panels for the Normandie in 1935; the latter, a mural for the teenagers’ coffee bar on the Canberra in the 1960s). Furniture by designers such as Robert Heritage, Ernest Race and André Arbus took pride of place on ocean liners, while architects Hugh Casson and Guillaume Gillet devised concepts for their interiors. In turn, designers took influence from these maritime interiors: Fauteuil Transatlantique, a lounge chair designed by Eileen Gray in the 1920s, was inspired by the deckchairs of ocean liners.

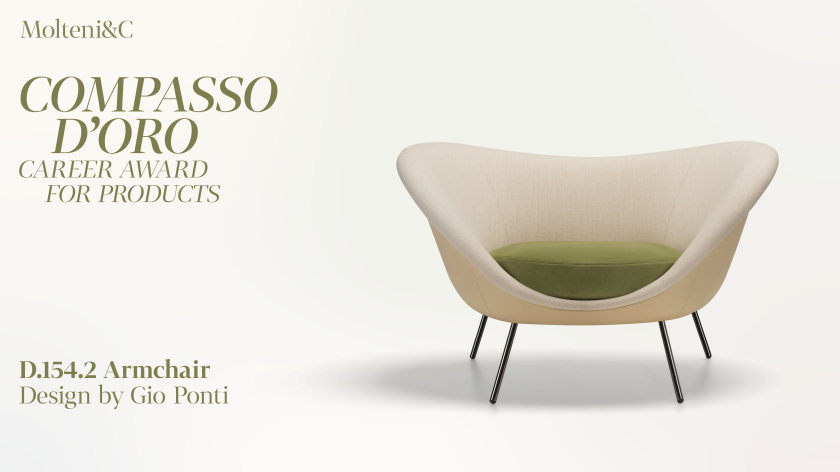

Perhaps most famously, Italian designer Gio Ponti was fascinated by maritime design in both a theoretical and practical sense. As founder and editor of the Milan-based design magazine Domus, he devoted two entire issues in the 1930s to Italian-designed ocean liners. He also worked on the interiors of several ships, helping to establish the international reputation of Italian modernism through collaborations with such figures as furniture designer Nino Zoncada, by commissioning notable artists and artisans, and through on his own designs, including chairs for the Conte Grande, the Augustus and the Oceania, among others. Last year, Molteni & Co. reissued Ponti’s D.151.4, an upholstered armchair with walnut and brass legs that appeared in some form on several ships, confident of the enduring appeal of the designs that emerged during this time.

The arrival of the passenger jet put an end to the golden age of maritime travel and, thus, nautical design. Today, the design of cruise-ships is guided by the principles of mass tourism, rather than long-distance transit. Meanwhile private yachts, the most luxurious and glamorous form of transport on water, are accessible only to a few. Air travel had its moment of glamour before the era of budget airlines and enhanced airport security, and some designers have turned their hand to aircraft interiors – Hella Jongerius’s business class cabin interiors for KLM is one example. But, perhaps because of the relatively short journeys and lack of public space associated with aircraft, they have never attracted the big-name interior designers in the same way as ships did. It’s a similar story with trains: designers such as Kenneth Grange, Priestman Goode and Barber & Osgerby have designed them, but recent train interiors primarily have function in mind: making a short journey in a small space as comfortable as possible, rather than allowing passengers to luxuriate in the moment.

This is perhaps why nautical briefs continues to have such a hold on designers and architects. In recent years, a host of big names have turned their hand to yachts – and not just because such commissions are lucrative. Philippe Starck – who grew up sailing with his father – has designed several, including a sleek aluminium boat for Apple’s late founder Steve Jobs. “I come from the sea,” he told the magazine Boat International last year, explaining his interest in nautical design. When Marc Newson revealed his first boat design for Italian brand Riva in 2010, he explained that it stemmed from his fascination with Italian post-war designers and their ability to seamless produce any type of industrial product, from furniture to vehicles. In 2016, when architect and avid yachtsman Frank Gehry realised a long-standing ambition to design a seafaring vessel – a 74ft sailboat for real-estate magnate Richard Cohen – his words were a reminder of the continuing emotive appeal of the open sea. “"On a boat like this, it’s about romance and romantic encounters,” he said.

And like their forebears on ocean liners, many designers see a nautical brief as an opportunity for experimentation. “As a dynamic object that moves in dynamic environments, the design of a yacht must incorporate additional parameters beyond those for architecture – which all become much more extreme on water,” the late architect Zaha Hadid said when she revealed her concept superyacht for German shipbuilder Blohm+Voss in 2013, which featured the sinuous curves of her architectural work.

Vincent Van Duysen, creative director of Molteni & Co, who has designed yachts under his own brand, echoes the sentiment. “Yacht design is very restrained: everything needs to be lightweight, demountable or to respect rules, and there’s a functional need for everything,” he says. “Often yacht interiors also have restricted dimensions, which means all proportions, thicknesses and relations between materials, shapes and details need to be carefully analysed and refined, and they combine many different aspects of design, from lightweight materials and advanced techniques to more traditional solutions based in refined materials and pure craftsmanship.”

Of course, technological developments in materials and techniques means nautical designers today have far fewer limitations than before. Van Duysen argues, however, that this has not necessarily been a positive thing. “Yacht design is dominated by soulless atmospheres, over-designed spaces and layers of decorative detail,” he says. “The expanded possibilities in materials and techniques means there are no limits, which can be counterproductive – some yacht interiors are overwhelming.” This is partly why the aesthetic of yachts today is associated more with conspicuous opulence than high design.

In contrast, Van Duysen’s approach has been to adapt, rather than alter, his broader design philosophy, bringing the clean minimalism, understated luxury and restrained palette of colours and materials that characterise his residential projects to his nautical designs. His June Boat, completed in 2012, and RH3, a 40m expedition yacht, both featured warm, neutral tones and materials like textured timber, marble, brushed stainless steel, leather and linen. “Besides all the glamour or adventure character of yachts, they are also your home at sea, where you feel protected,” he says. “Designing a yacht that could be lived as a floating home as very appealing to me.”In that respect, his approach to nautical design has echoes of a previous era, when seafaring vessels were seen as microcosms of or models for land-based architecture.

Perhaps most strikingly, mainstream designers are bringing an approach to yacht design that draws on neither the opulence of ocean liners, nor the flashiness associated with recent yachts and cruise-ships. Whether it’s the refined, understated palette of oak, leather and onyx of Foster + Partners’s boat for Alen Yacht or the clean lines and pale interiors of John Pawson’s work – the simplistic proportions and naturalistic, domestic interiors of these seafaring vessels reflect our the contemporary notion that luxury is intertwined with comfort, calm and sensuousness rather than over-expressed glamour.